Spanish with English subtitles

With Jairo Fuente, Wayúu village community

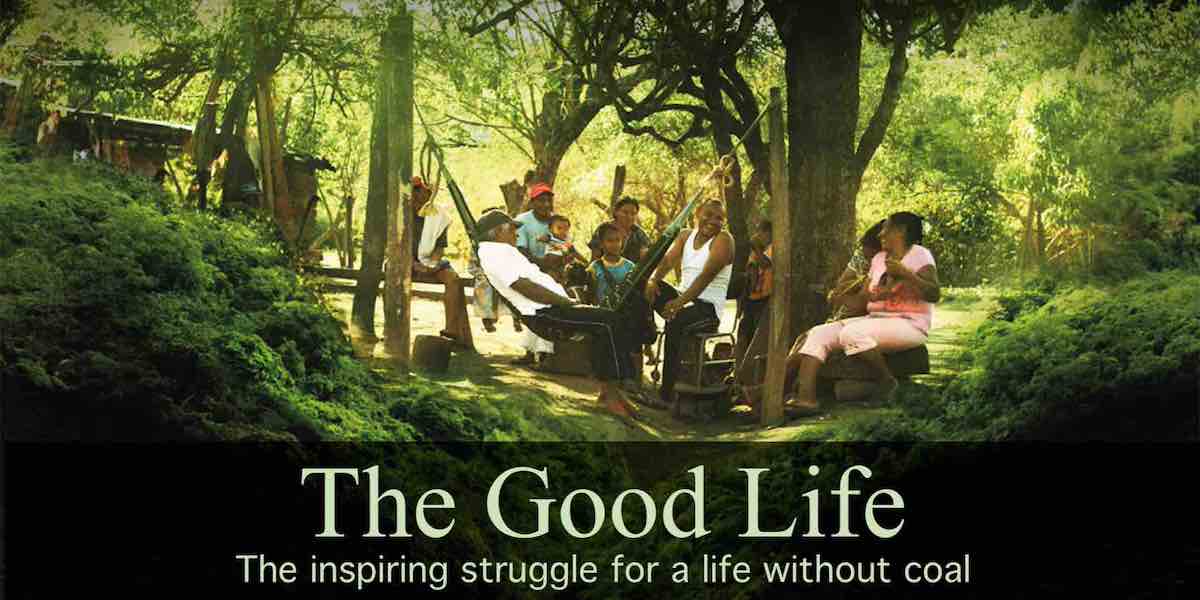

The village of Tamaquito lies in the forests of Colombia. Here, nature provides the people with everything they need. But the way of life of the Wayúu is being destroyed by the vast and rapidly growing El Cerrejón coal mine. Determined to save his community from forced displacement, the young and charismatic leader Jairo Fuentes sets out to negotiate with the mine’s operators. They’re backed by powerful global resource companies such as Glencore, Anglo American, and BHP Billiton, and communicating with their representatives isn’t easy. The villagers are promised the blessings of progress, but the Wayúu place no value on modern, electrified houses – on the so-called better life. Instead, they embark on a fight to save their life in the forest, which soon becomes a fight to survive.

About the Director

Jens Schanze was born in Bonn in 1971. After completing his civilian service, Schanze first studied forestry in Munich but then moved to a television production company. He made his first film in Bolivia for an environmental foundation. He and his cameraman, Börres Weiffenbach, won the Adolf Grimme Preis in 2002 and the Bayerischen Fernsehpreis for Otzenrather Sprung. In the same year, together with Judith Malek-Mahdavi, Schanze founded the production company Mascha Film in Munich.

Notes on Film

“In 2011, for the first time, Colombia became Germany’s main coal supplier. This prompted me to undertake a research trip into the coal mining regions of this South American country. The psychological condition of the villagers affected by coal mining was shocking. They were distraught, paralyzed by a feeling of powerlessness thanks to the mining companies’ often ruthless behavior. They were also suffering the consequences of mining: dust, noise, water shortages, and resultant crop losses, along with the threat of losing their homes and land. What’s more, people everywhere have lost their sense of togetherness. The companies had succeeded in weakening or destroying the village communities and creating a situation in which organized resistance was impossible. In the face of existential threats, every family was fighting for its own survival. People couldn’t expect to receive any support from state institutions: on the contrary, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos described the mining industry as a driver of development in his country. Special divisions of the Colombian army were stationed in the mining regions to ensure that nothing was allowed to disrupt the operation of the coal mines.

Tamaquito was faced with just as many threats as the other remaining villages. Here, though, the mood was completely different. There were no signs of resignation. The community seemed strong and self-confident. It was led by a young man who radiated quiet authority and self-assuredness. How had these people succeeded in maintaining the integrity of their community and negotiating on an equal footing with representatives of the mining companies? I had a small research camera with me and, as I filmed in Tamaquito, I knew that this was where I wanted to make the film. Our group’s visit lasted only around three hours. When it came to an end, I asked Jairo Fuentes, the village’s young leader, if he could picture us recording Tamaquito’s resettlement process. He responded that it was a decision for the village’s general assembly. He also said, “But I see no problem with it. We’re fighting the same fight”. These were our parting words in September 2011.

The general assembly of Tamaquito agreed to the project. It took more than a year to develop the film proposal and raise most of the necessary funding. In January 2013, we finally began filming in Tamaquito.”

– Jens Schanze, Director